An article From, Meghan Newell Reedy

Meghan is a student at Aikido of Maine. She is 1st kyu and we are all waiting for in-person training so she can take her shodan test. We hope you enjoy this article as much as we did.

I was walking around in that feeling of falling all the time, having been knocked off balance by a difficult move from one city to another, spun by my father’s stroke, blown over by the way the time comes for one career to end and some other way to begin like it or not, no choice, here I come; all ordinary things that could happen to anyone. And so when I saw the sign that said Aikido: The Art of Peace: Martial Art & Fitness I thought okay that’s the thing, because in movies the chaos swirls around but the person in the swirl’s still center stands calm and sure and does what needs doing until the chaos is quieted, and I wanted to be like that – calm and sure and standing in the still center of my life, instead of tripping and gasping at its edges. So I walked in ready to learn how to do that.

But that, it turns out, is only half of it. Aikido is a non-competitive martial art; in executing a technique one aims to protect both oneself and one’s attacker from harm. In aikido, nage, who is attacked and diverts it, stands their ground while uke, who attacks and is diverted, falls. Each responds to the other’s contact and movement, each confronts their own temptation to struggle or to run away. Both bring their full presence to an attack and its defense and together transmute it into a moment of real grace. And one way to practice this powerful, difficult thing is by taking turns attacking and being attacked, standing your ground and falling.

Meghan Newell Reedy

Of course it’s obvious as soon as you see it, but when I stepped out onto the spacious, gray-green mat at Aikido of Maine on that very first evening, it took me by surprise. Half of practicing aikido is doing this embarrassing thing, falling down over and over again! Plus every time you fall, you have to get up again, and as it happens falling down and getting back up over and over uses pretty much every muscle and fiber, every joint. It’s exhausting. But also, unaccountably, even in that very first class, actually finding the ground over and over pushed back that awful inner falling feeling just a little ways. Some of the dust of habitual dread got knocked off, some of the layers of anxiety cracked here and there and joy just bubbled through as though it was always there and waiting. I hadn’t expected that joy, but there it was. Bubbling gently up, unbidden

The falling business came easily to me, I who was a falling prodigy as a child, a bona fide expert. There was the full speed fall in a puddle on asphalt (classic knee scar). The fall from the highest bar on the orange jungle gym (mild concussion). Multiple falls out of sheer exhaustion (as after a long day of constant swimming) or convenience (after being thudded accidentally on the head with the back of an ax, for example). It’s simple, really. There’s the beginning of a fall, the moment when it flashes through your mind that now, again, you are more object than subject, more mineral than animal. There’s the middle, when all there is to do is flail and notice once again that the pieces of yourself come apart this easily. Then there’s the relief of landing, when you feel the pieces of yourself slam back together against the ground. All you need is a reckless taste for being an object in motion and a practical disinterest in pain. If falling was part of the deal in aikido, so be it. Let’s go.

But as I started learning to keep my shoulders from clunking the mat when I roll, my knees from splaying out in ungainly ways, bit by bit it became apparent that all this time I had unwittingly continued using my object-in-motion way of falling as my template not only for things like tripping in the hall or missing a stair, but for responding to almost anything. I was responding to my father’s stroke-fallen face and my mother’s despair, my wrenching move, my terrible fear of failing at life, as though I were falling

off a jungle gym or slipping hard in a puddle: I was flying apart, bracing for impact, waiting motionless for whatever reassuring pain might blossom on landing. The exultant early way of falling I was good at was, it turned out, gravely flawed. It was a reckless, hopeless, sacrificial way.

And so, after being told and shown a million billion times, I begin at last to learn some very, very rudimentary things, very, very slowly. I begin to learn that The most important thing is to fall safely. I begin to learn Take care of yourself. And also Don’t get hit in the face. Move your face.

When my teacher first says don’t get hit in the face it occurs to me that it hasn’t occurred to me before that I could do this, that I could move my face so it wouldn’t get hit. How can this not have occurred to me even here, where the explicit goal is to practice not getting hit in the face when someone tries to hit you in the face? I am stunned at first, and then enfolded by a wordless sorrow. Why fall so easily other times, but not now when falling is the swiftest way to safety? Stubborn refusal to yield? Bleak acceptance of inevitable harm? Are these just versions of the same misplaced notion of strength? But strength that lasts is woundable and knows it, that’s why it’s supple and moving and alive. I must keep training.

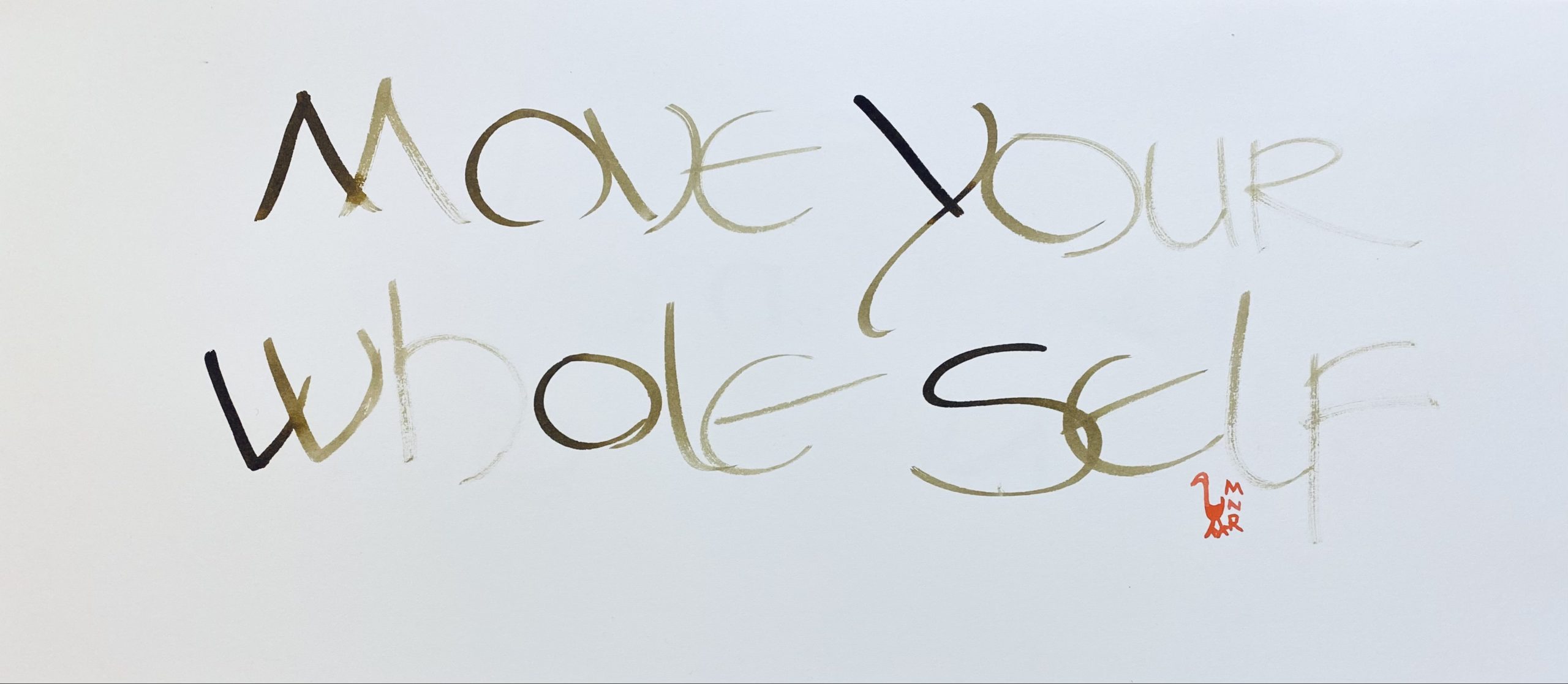

I start in on the long process of coming to see You are one thing, not pieces. Your arm is also you. You cannot leave it behind, so you must move your whole self. Your whole self moves. How can this be so difficult, when it is so obvious? But it is so difficult. Flying into pieces, leaving behind an arm, or a leg, or my face feels so easy. Whisking my whole attention right out and away and leaving behind the whole kit and kaboodle feels easiest of all, sometimes. Fly apart. Fall down. Get away and let nobody know. But no. I am one thing, even so. And it is also very difficult to learn Stay stable. Don’t just fall just like that. Stay stable. Keep moving. Still stable. … Now go.

It is Stay stable … Keep moving … Now go that makes the art of falling not an art of sacrifice, but a way to freedom. Stay stable to keep yourself from harm, to maintain your own integrity, to keep as many options open as possible, to find the ground on your own terms. Keep moving to stay safe and whole. And when the time comes, but only then, fall for these same reasons: to keep your options open, safely, and find the ground on your own terms.

All of this happens separately from everything else in my life. When I go to the dojo to train, I put on my uniform, a gi like one would wear for judo or karate, and after a while a hakama, the awesome, wide-legged trousers samurai used to wear. I bow before stepping onto the mat, and again when I get there, and again more formally when class begins. During class there is very little talking, and an expectation of full attention. The practice is physical, not mystical. ‘Take care of yourself’ is physical, as in ‘take care not to let your arm be hyperextended’, or ‘take care not to get punched’. Literally, physically, take care of yourself. And then a bow to mark the end of class, before leaving the mat, the dojo. All these steps help to separate the space and frame of mind where training happens from everything else that one does in a day so clearly that you’d think it would stay there.

But it doesn’t. It is a lovely, slow surprise that what I discover in this spare and focused space … pervades. Out of sight, without fanfare, quietly and in my own time, I also cease to approach my new work each morning in dread, ready to leave immediately in case the kind, calm people who hired me change their minds on a whim. I begin to eat more food and breathe more air. It is as though the rest of me learns from my muscles and my bones those things it is not possible for me to learn by thinking or talking or wishing.

Still, I find it terrifying, like hearing noises in the dead of night, like seeing ghosts, to begin to begin to Feel what is actually happening.

Yes. Feel what is happening. Actually feel what is happening. This is the key, the essence of the thing, but the fear is blinding. As with so much of what I learn in aikido I cannot learn this by thinking it through or puzzling it out. I have to be still and wait for it, accept it, do it, which is much much harder. I have to keep my eyes open for it without actually looking, the way one watches through the night for the dawn, which breaks when it breaks. At last I seem to see the palest silvery glimmer of Feel what is actually happening start edging out the edges of the dark.

Difficult, terrifying, slow going, but always with this brightness underneath, always joy bubbling gently, persistently, to the surface. And it turns out all these new and basic things are not wholly new, in the end, nor actually basic. They point towards something bright and springy and joyful that was always there: Just fall. Don’t force it, don’t anticipate, just see what happens. Just fall. Because in those rare moments when I can manage to just fall without flying apart it is effortless and glorious. There is no astonishing beginning, no flailing in the middle, no relief in landing, because the difference between standing and falling has disappeared and I am just there. Everything is in motion and everything is alive, and for a brief instant it feels true, what O Sensei, the founder of aikido, used to say: I am the center of the universe.

***

Mitsugi Saotome Shihan trained intensively with O Sensei, Morihei Ueshiba. He tells how one day he walked into Ueshiba Dojo and bowed and Ueshiba was chatting with some students after class but looked up anyway and called him over. Saotome Sensei chuckles and says how his life had been going this way this way this way, but from that day, shoom – his arm points off and out, at full extension – from that day his life went that way, a different way. He became one of O Sensei’s uchideshi, living and training at that dojo for the next fifteen years, until O Sensei’s death. Mitsugi Saotome is a linchpin in the transmission of aikido on the East Coast of the United States. He is my teachers’ teacher. He is eighty-something now, straight-spined and poised and intent even though his thoughts have begun to loop. Just once I shook his hand; warm and full and perceptive.

An advantage of his looping, circling thoughts is that a listener like me has a chance to hear him work through a few things often enough that they have half a chance of sinking in. He thinks, for example, about the power of very small things. About insects and the atom bomb. How very small things can have very large effects. I was outside clearing some space for a garden, was one way he came to it. I was clearing some bushes and I didn’t see the wasp’s nest until I had disturbed it. I was destroying his home. So of course the wasp came to defend it, he came and attacked me – and I go like this like this. He runs a few steps backwards and flails his arms. Tiny wasp! When he says ‘wasp’ he adds a vowel between the adjoining consonants in the Japanese way, so it takes a moment at first for us to catch his meaning, makes us reach for what he is saying. Wasip only this big! And see what I have to do! He pauses. Waits a moment. Wasip Shihan. Very great teacher. Wasip very great teacher.

This story is looping in my mind now, looping and looping. Virus Shihan I keep thinking. Tiny, tiny virus, only this big and see what we have to do. See what we have to do.

***

On Friday things were strange but open. But on Saturday all of Portland, Maine closed down. Shut. Our dojo is shut. We cannot step onto the mat together now, for now. Cannot go trough the steps of stepping into that space so carefully set aside for practicing all the powerful, difficult things I somehow could not learn any other way. The transmutation of conflict into grace. The cultivation, against one’s every instinct, of the awareness that conflict is also a part of the grace of things, sharp and intent. And also infused with joy. We cannot step onto the mat, day after day, and train together to attune ourselves more finely and more gracefully to the world. How will I practice don’t get hit in the face? How will I practice take care of yourself? I cannot practice, I cannot practice, I cannot practice.

On Saturday the dojo shut. On Sunday there it was, stealing back all at once, that feeling of falling my old way – claws on my collarbones, that cage around my ribcage squeezing out my breath, that bar flat cold across my shoulder blades.

Clamped down. Shut.

That’s it, I thought. Like a racehorse stuck in her stall, a greyound locked in her crate, a wild boar surrounded by baying dogs.

Wait, no, I thought. No. No no no no no. This seems different but it is not different. I have been training all this time for nothing else but this. I have been training all this time to meet this moment, this very moment, the moment that is always unfolding, which is always now. The dojo is closed but it is not shut. It has been blown wide open. We are all uchideshi now, living and training in this blown-open dojo. This ground right here, I thought, this ground beneath my own two feet, this is my training ground now. And now, now I will practice, clamped collarbones and all, now I will practice feel what is actually happening, and I will fall when it is time to fall and not before, and I will find my way to the ground, this ground, on my own terms. And who is my training partner now? Same as always. The opponent, really, is always one’s self. I will keep training.

***

But how could I train when nothing was happening?

I went nowhere. I saw almost no-one. A crushing silence descended on our house, yawning wide between my husband and me. Not unfriendly, not pointed, but wide and deep and quiet. I brought my work home and I did it, but everything happened on my computer or over the phone, so my desk always looked almost exactly the same – as though no-one ever did anything there. It was like sitting too still for too long in the bath tub, how you stop feeling the water. You have to slosh the water with your legs and arms and slowly sit deep down and then sit up again quickly from time to time just remind yourself that there is water there at all.

Everything was still. It is so still.

I cannot bear the stillness, so I try to slosh at it with motion. I move constantly, I am ruthless, but it doesn’t matter. I walk barefoot into the snow-patched grass in the morning and practice breathing in angular patterns. I jump rope and run and stretch midday. At night I stretch again and roll on foam rollers and then practice breathing and moving in slower rounder patterns. Still the days ooze by and every hour is identical to every other hour of every other day.

Three days a week the dojo comes to the computer screen, each one of us in our own little square, in whichever room in each of our houses is least personal to show. We do what we can. It is better than nothing, but it does not seem to stop this thinning out of all the lines that keep things separate and themselves. The line between day and night, today and tomorrow, my foot and the floor. It all runs together into murk.This place where I am now, on the rug in my living room, which is my dojo, where I am uchideshi, is not clean or spare or bright. It is not separated out by anything at all from anything else in my whole life. Everything happens right here, but leaves no trace. Everything presses in from everywhere, but makes no noise.

***

Though it is inconvenient, because nobody really has room at home, my teachers begin to focus heavily on sword work. Most of aikido is empty-handed practice, but training with a wooden practice sword, a bokken, and with a shoulder-height wooden staff, a jo, have an important place. Training with weapons galvanizes the attention and drives home the need for good timing and good distance. Weapons up the ante, when you’re training with a partner, and demand you practice with the willingness to die. Now they give us something clear to do with our hands and a visceral sense of how low the ceiling really is.

I add suburi, sword cut practice, to my afternoons. I order a weighted practice sword, a suburito, to make it harder. I add incrementally, day by day, starting with 50 cuts, and get to 800. Still it is so quiet. The quiet is enormous and I cannot get out from under it. However much I move, no matter what I do, I am pinned here. All day every day, my face is pressed against the ground that is my life with this silence ringing in my ears.

Fatigue is another thing Saotome Sensei thinks about. The way that when a person starts to tire out, it’s their attention that thins first, then falters and scatters, while the muscles and lungs and the rest keep going. It’s the attention that matters most, and it’s the attention that goes first.He often brings this up at the end of a long day of training, at the end of a week of long days, and he says You are exhausted. The enemy is very happy. He uses the wrong participle though, by mistake, so the word he actually says is ‘exhausting’: You exhausting!

Now, training relentlessly, uchideshi in the dojo that is my life, training always and always and only and only with myself as training partner, I see that his phrasing was not a mistake at all. I am exhausting. Exhausting. I cannot find the timing. I am always too late, always I have already felled myself with anxious angry second guessing or pinned myself down with straight grief. I cannot get any distance from myself. I am being hounded and run to ground by myself, and not on my own terms either. Who is this exhausting me that does this to myself? I cannot train with this person. She is exhausting. She is too much for me. I am exhausted and my enemy is very happy and my attention, the thing that matters most, is fraying very badly, battering around like a fly in a bottle. I want to leave this dojo after all. Please. Let me out. Let me leave. But it is too late. I have already begun to feel what is happening, and un-feeling things you have felt is like un-seeing things you have seen or un-knowing things you already actually know. It isn’t possible. I must keep training. Here. I cannot leave this dojo because it is my life, and I have begun to feel what is happening when nothing happens.

***

In between the doings of my day, things waver and muddle their way in and out of focus. How I left the room where my father lay dying and he raised his hand as much like always as he could and said ‘bye Meg’ and then I turned and left. How I left and then just ten days later he was pushed into the oven to be burned away to ash. How I went across the country with my mother who was hollowed out with sadness and relief to move her all that way back home and left her there. How long ago and far away that first time when my parents moved us all decisively away from everything I knew as home we had to leave the cats behind and all the records and the record player and my one True Friend. How well I’d learned that wanting what I wanted wasn’t worth it in the end because it only left an opening, a soft place like a dragon has just there where there’s a missing scale or two. How well I’d learned to read the shifting winds of others’ expectations and to sail by them and them alone. All the little losses and denials I’d stacked up as thin as shadows one by one to keep the big things in.

Yes.All this. I have tried, I see, it seems, to leave a thing or two behind and walk away. I’ve done that, yes. But no, I am one thing and so I can’t in fact have done that even if I tried. I am one thing. All this, I see, all this is also me. All me.But wait. I know this! You can’t fool me with your wavering and muddling. Why dig that old stuff up? Why open up old wounds or pity old misguided mess-ups? Best to let bygones be bygones and the past is the past and that’ll be that thank you yes. After the third, the fifth, the seventh new school new house new town new state, of course I knew to box the last one up and leave it on the empty doorstep as I walked away. No baggage. No carry-over. Start afresh is the most reliable rule. Expect nothing want nothing ask nothing from anyone. Never be surprised. Never mind. Never prefer. Never wish. Never ever regret. Plus I was a child then! A child! So long ago it hardly matters now. Simplest not to dwell on what was left behind. On who got pushed into the darkness of my mind or why. Just look away. But I couldn’t now. It swelled into an oceanic grief, and I felt it happen. It came in rolling waves or welled up from the ground or just appeared and spread as though a huge clay jar had burst against a wide tiled floor. I have no good words for this as it is happening. I sit on the rug in the living room and weep and see that I am thinking O so this what it is to weep. There is so much water. I rock back and forth as I sit, like a child, like a person stricken with grief, like a ghost.

***

I hear a version of my teacher’s voice echo and re-echo in my mind, saying you are all one thing, not pieces. You cannot leave one part behind. Move your whole self. But what I feel is this feeling of losing definition. I am thinning. I feel the particles of myself drifting apart in clumps. I am coming apart. It is so quiet I can hear the parts of myself creaking as they drift and roll in the empty space where my life used to be. You are all one thing. I am nothing.

Every day every day every day my face is pressing pressing pressing into this nothingness that is my life. And the only way to get up will be to learn this thing at last that I am one whole thing nothingness and all. The only way to move is to move my whole self nothingness and all. So I drink tea. I practice sword cuts all alone. I sit on the living room rug and look at the fattening leaves on the oak tree outside. I breathe in and out and in and out.

This does not look like aikido. But this is also aikido.

***

That massive grief washed through for weeks. It rose and fell and rose again, an erratic tide scouring a weary beach. I watched it come and go. I felt it happening as best I could. And then I felt the gaps that grief was rushing in to close – the gaps between these pieces of myself which were not pieces. They hadn’t drifted off, I realized; I had pushed them all, and at great cost. Of course I had.

It’s so personal, the will to live. So revealing, so fragile, I had to swaddle it, I thought, in these pieces of myself, in layers. The mortifying power of the desire to be all the way alive, the flare and glow and pulse of it. The way it drives the roots of trees into the living earth and presses flowers to the sun.

Think of the strength it takes to keep it down.

Think what would happen if I let it have its way.

What would happen?

***

It is one of the things Saotome Sensei says, I think, but I only heard him say it once. He dropped it like a pebble in between the other things his mind was looping on one day. He said You have to trust yourself. You must be able to trust your self. Which means you must be someone you yourself can trust.It changes nothing, but everything seems different – the same way nothing changes when the light expands at sunrise. That silence yawning out between my husband and myself has ended now. We’ll go our separate ways, but each of us is wholer than we were. Another silence ended too, between a woman I love and me, and we’ll see what happens as we move ahead together, each of us as whole as we can manage. But these are ripples, really, at the very surface of what’s happening. The current of what’s actually happening runs swift and deep and full and out of sight in each of us. I must keep training.

***

When summer comes at last, we start to train at weapons in the dojo parking lot. We gather at our same three times, a few folks still joining in through the computer. We know it is precarious and unlikely to stay this way, here in Maine where winter will be dark and cold, but we do it anyway: all in masks and in the sun and wind and on the tarmac. We gather every time we can and at the start and end of every precious class, stand silent, bow together, breathe. The line between the rest of life and training is visible again, for now.It is such a gift to have a training partner raise their sword and aim at me and bring it down. To feel the ground beneath my feet and how it lets me raise my sword in time to meet that blow, this time. How I have to stay still and be willing to die right then right there and at the self-same time feel all of me fill up with joy and raise my sword and overflow with livingness and live.

***

Recent Comments